Background

Over the course of the past 10-15 years, machine learning, and more specifically computer vision (CV)

has had a major impact on many industries and the consensus is that it will continue to disrupt and

revolutionize more and more facets of everyday life. Already, CV systems have shown promise and even

superhuman performance in areas ranging from driving to medical diagnosis. They are able to do this by

leveraging massive amounts of data and complex algorithms that can be trained to complete a specific task,

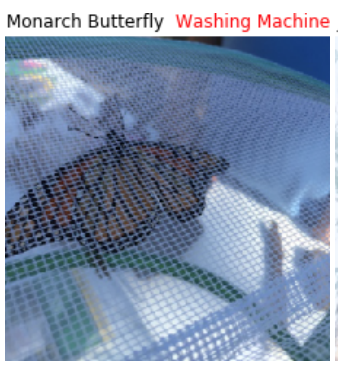

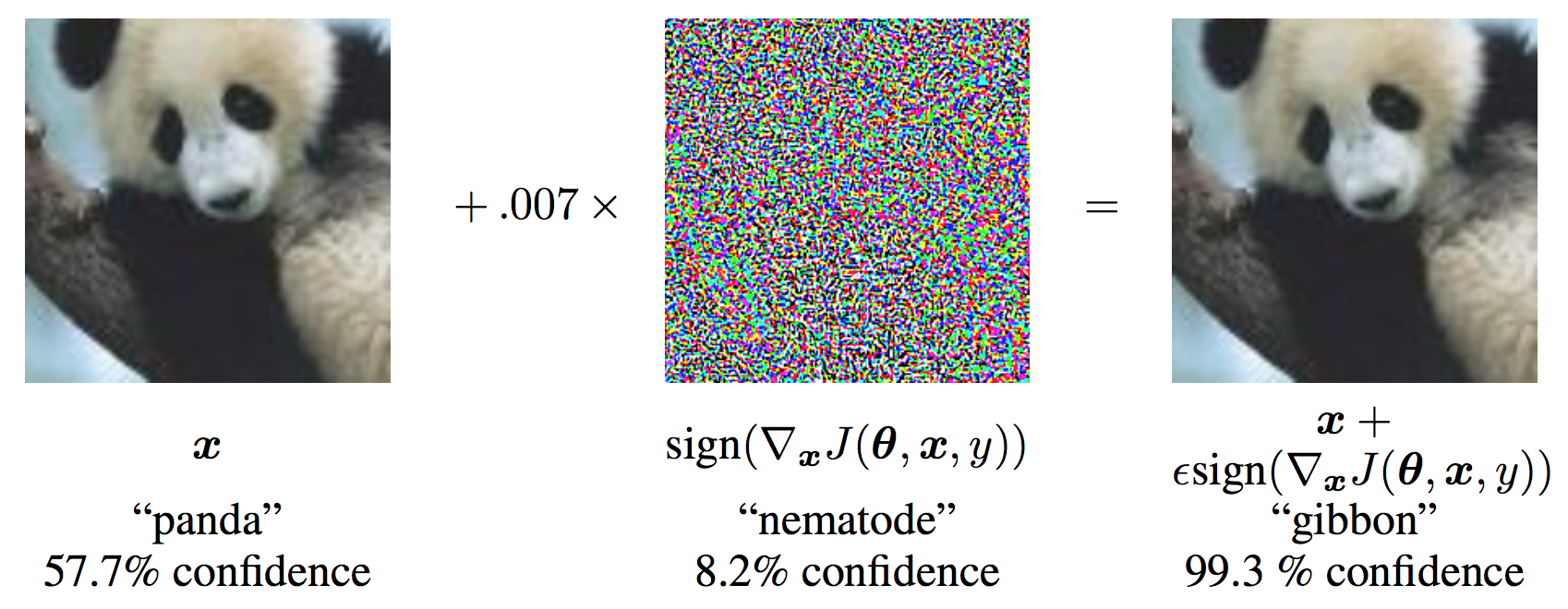

recently, however, a serious problem has emerged. Look at the following example:

To a human, theses look identical. Same animal, same pose, same lighting, etc. But to a state of the art

neural net, the image on the right looks like a gibbon. This net, which routinely outperforms humans, is

more than 99% sure that the picture on the right is a gibbon. What could be causing this?

To a human, theses look identical. Same animal, same pose, same lighting, etc. But to a state of the art

neural net, the image on the right looks like a gibbon. This net, which routinely outperforms humans, is

more than 99% sure that the picture on the right is a gibbon. What could be causing this?

CV systems don't 'see' the same way humans do. If asked, "how do you identify a stop sign?", most humans would likely answer something along the lines of shape, color, and the word 'stop' written on it. Neural networks don't operate the same way, they look at features that aren't necessarily salient to the task but allow the model to pictures easily. In practice, this means that they often rely heavily on texture and other aspects that a human wouldn't consider the most relevant features for identifying an object. Clearly, this has some advantages, as evidenced by the system's performance on any number of standardized tasks, however, there are also significant drawbacks. The texture can be subtly changed or 'perturbed' in such a way that it fools the system into thinking that a picture is something it is obviously not. This minor perturbation doesn't affect a human's ability to recognize a picture, and often isn't even noticeable, but it absolutely destroys a computer's ability to make sense of an image.

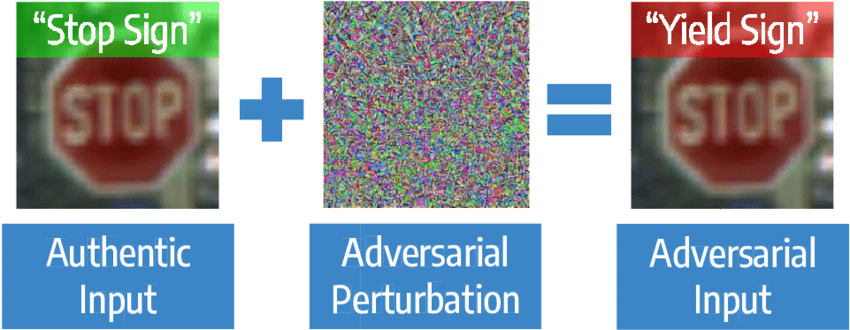

These perturbations can be introduced to the system in two main ways: targeted or natural. Targeted

adversarial perturbations are difficult to defend against especially if the attacker has access to the

original model. There are many mature techniques for attacking theses systems and an effective defense

against them is still an open problem in the field. Applications of these attacks can be dangerous in the

right situation. Many self-driving cars rely at least partially on computer vision, which we know is

vulnerable, so if a creative attacker managed to perturb a stop sign in a specific way, they could cause

the car to perceive the sign as a 50 mph and accelerate instead of stopping.

There are many other applications of this approach but targeted attacks are largely out of scope for this writing.

There are many other applications of this approach but targeted attacks are largely out of scope for this writing.

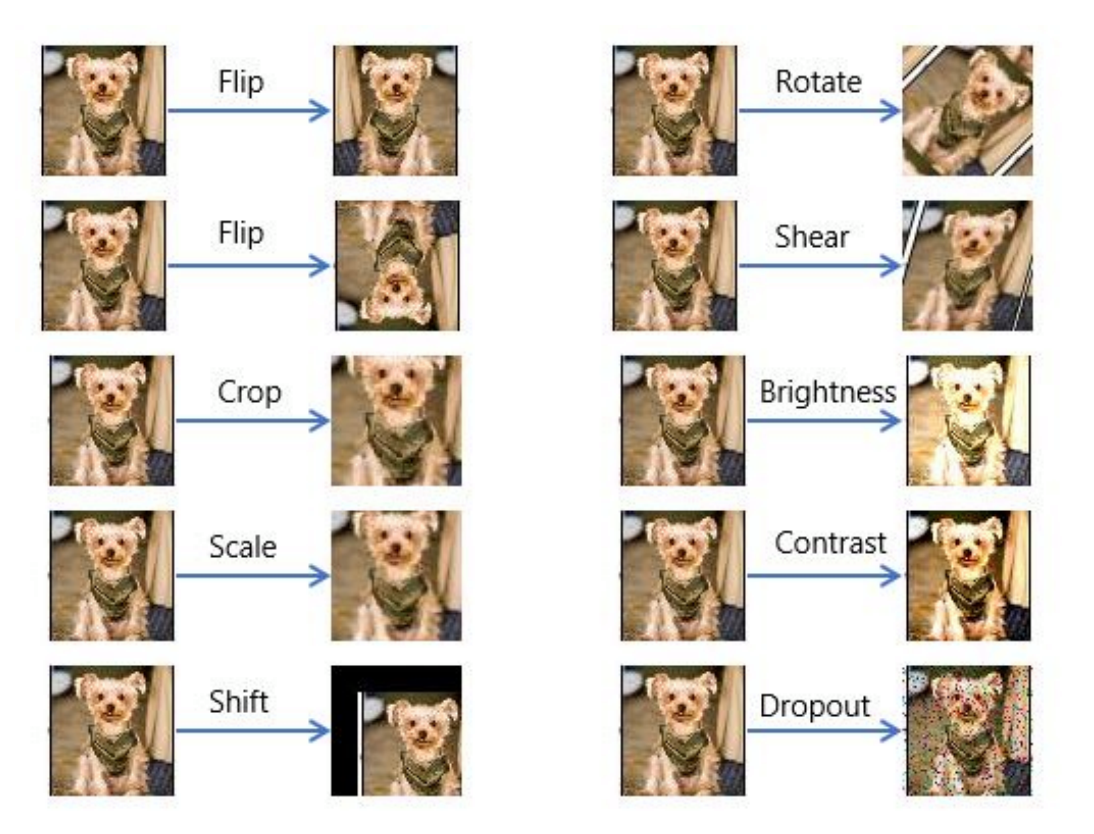

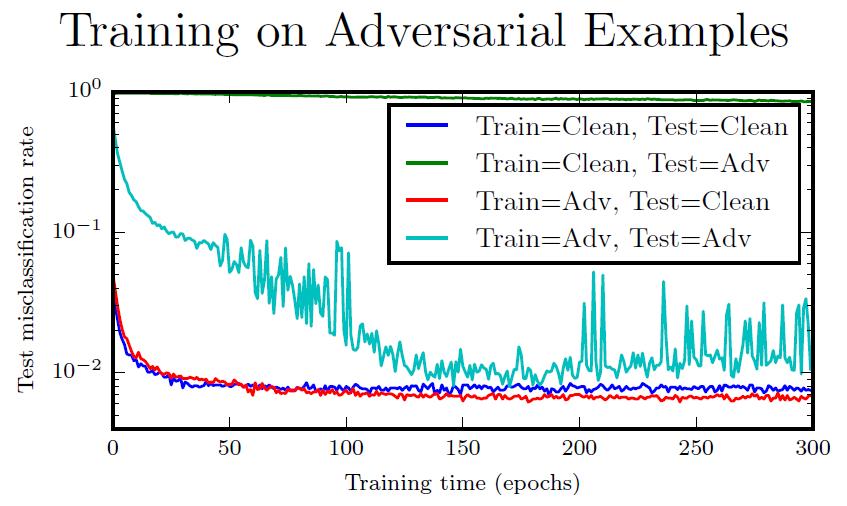

Our approach is a training method for defense against natural adversarial examples, which are broadly

defined as images that aren't altered post-photography, but that cause significant and unexpected problems

for CV applications. These are slightly easier to correct for as they are not designed to cause problems.

If we can identify and reproduce the problem, we can simply retrain the network with these examples as well

as the original training set. This is called adversarial training. Adversarial training has been used for

defending against targeted attacks as well but its efficacy is somewhat limited.

If we can identify and reproduce the problem, we can simply retrain the network with these examples as well

as the original training set. This is called adversarial training. Adversarial training has been used for

defending against targeted attacks as well but its efficacy is somewhat limited.

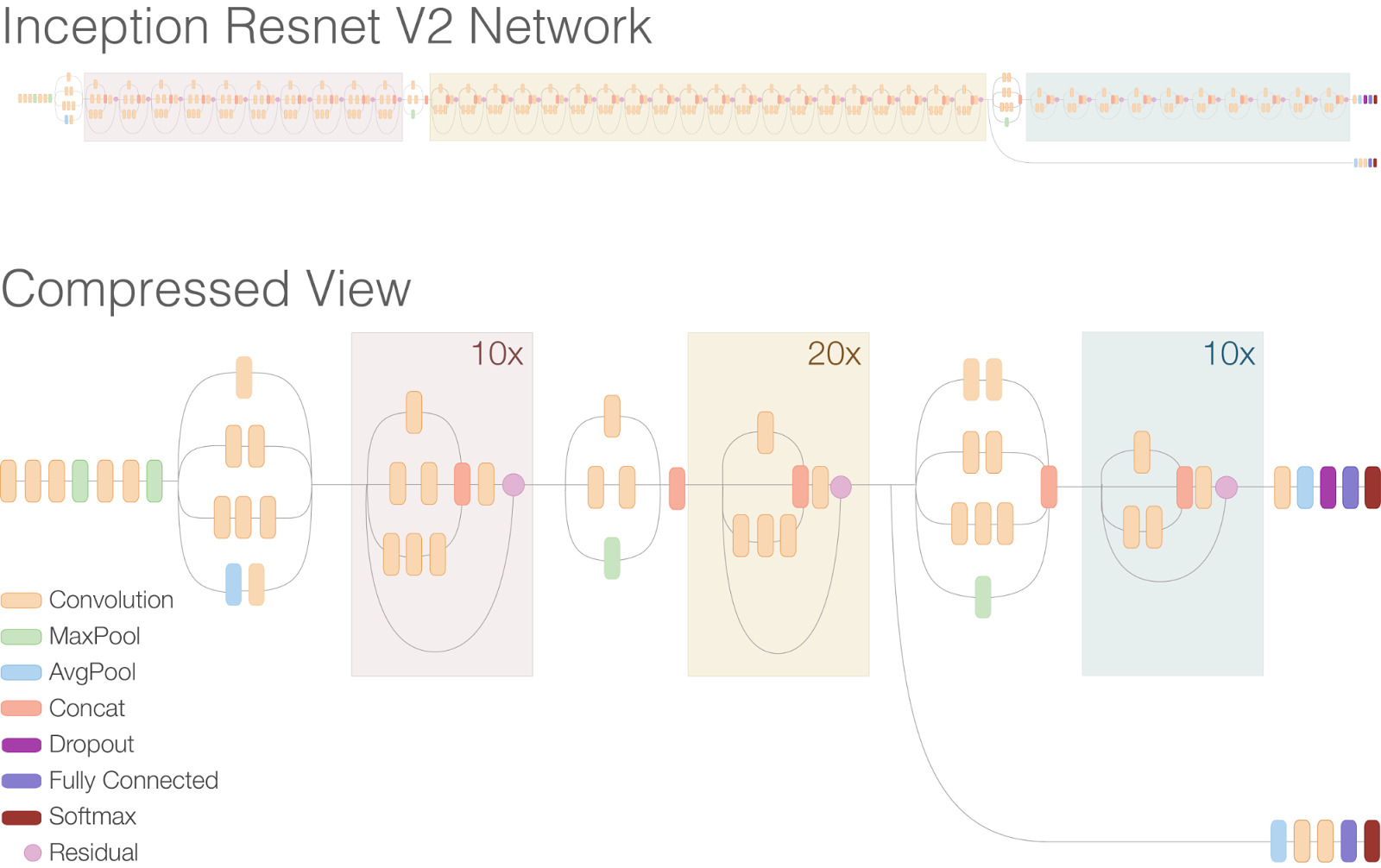

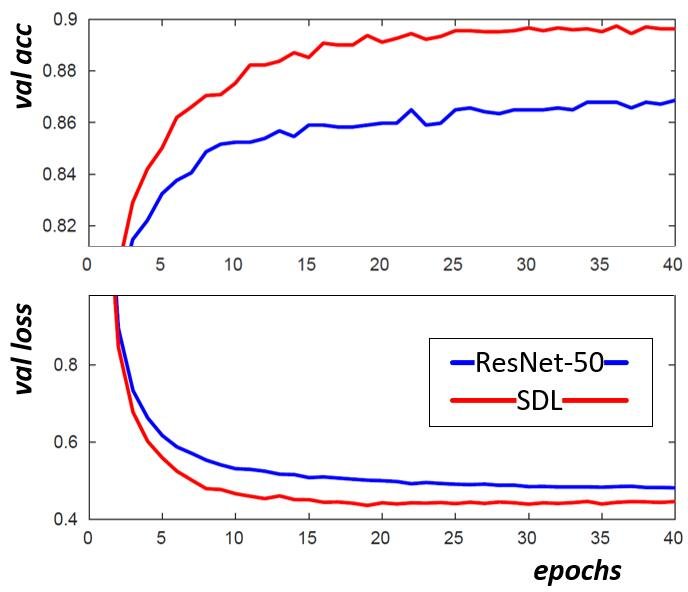

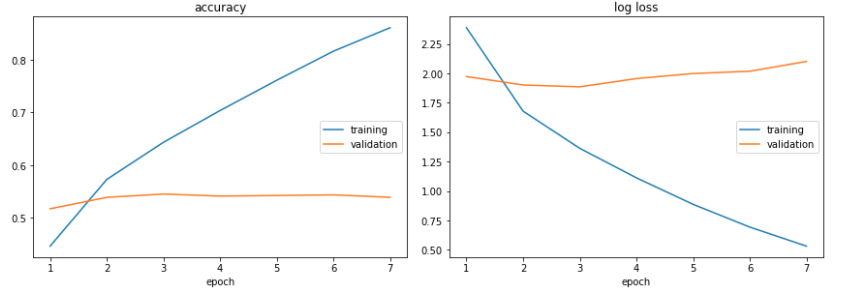

In this repo, we develop an image recognition system based on res-net and the tiny image-net dataset that is somewhat resistant to random natural perturbations. We show that our training method is effective at improving the accuracy of our underlying model when testing on cross-validated tiny image-net data which consists of 100,000 64x64 RGB images spanning 200 classes for training and 10,000 similar images for validation.